The Perfect Album at the Perfect Moment

30 years of Rachel’s "Music for Egon Schiele"

I was sitting in the living room of the musician Will Oldham in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky about seven years ago. The house we were in served as an auxiliary space; it had been his home, but he’d moved his family to somewhere a little bigger and kept the smaller place as a sort of workshop/storage space that was littered with CDs, books, and instruments. I first became a fan of Oldham’s around the time the album that a lot of people initially discovered the highly productive songwriter, I See a Darkness, came out. It was officially released in January of 1999, so my guess is I first heard the album later that year or early in 2000. Either way, I hadn’t yet totally pieced together the map that tied Oldham to other bands and sounds from Louisville that I was already familiar with, specifically the band Slint and countless other groups their music influenced. Their second album specifically, 1991’s Spiderland, serves as one of the foundational records for a number of subgenres that music critics still like to use—post-rock, post-hardcore, math rock, etc.—none of which even come close to describing anything Oldham has recorded under his name or various monikers like Bonnie “Prince” Billy, Palace, Palace Songs, etc. In case you’re not familiar, Oldham’s best-known work tends to be a mixed bag of gothic country, Appalachian folk, often with a more lo-fi indie thing in terms of recording.

But look at me: I’ve gone and sounded like a music writer with that long-ass intro and all those silly labels I put on everything. It’s annoying, but the broader point is I’d always been curious, since Oldham took the now-famous photo of Slint on the cover of Spiderland and had been a longtime friend and collaborator with a few of the band’s members, what it was about Louisville that made it one of the more vibrant, and often overlooked underground music scenes in the country. Besides Oldham, Slint, and the many offshoots connected to those groups, Louisville had this sort of mythic status in the ‘90s to kids like me because they had these other little scenes-within-the-scene that defied the expectations of the day. I don’t know if Crain shared members with any bands, but I’d argue their records should be as appreciated as anything else noisy and post-whatever that came out of the mid-1990s, and I won’t rest until I’ve told everybody on the planet to seek out the 1994 indie film Half-Cocked, which partially takes place in Louisville and stars members of the scene from those days. The hardcore scene I knew about from zines and on message boards had included foundational bands like Endpoint, Enkindel (later rebranded as The Enkindels after a member left), and Falling Forward, that went on to start other bands like Elliott, By the Grace of God, and Metroshifter. Most of those bands played—in my mind—a smarter, more emotionally brand of hardcore that, yes, could maybe get lumped into the “emo” section of a record collection that, when you add together the Slint sound, helped reshape American underground music. (Also, if you never got to read my piece about the indie rock godhead house parties Bob Nastanovich used to throw during the Kentucky Derby when he lived in Louisville, it’s a good one.)

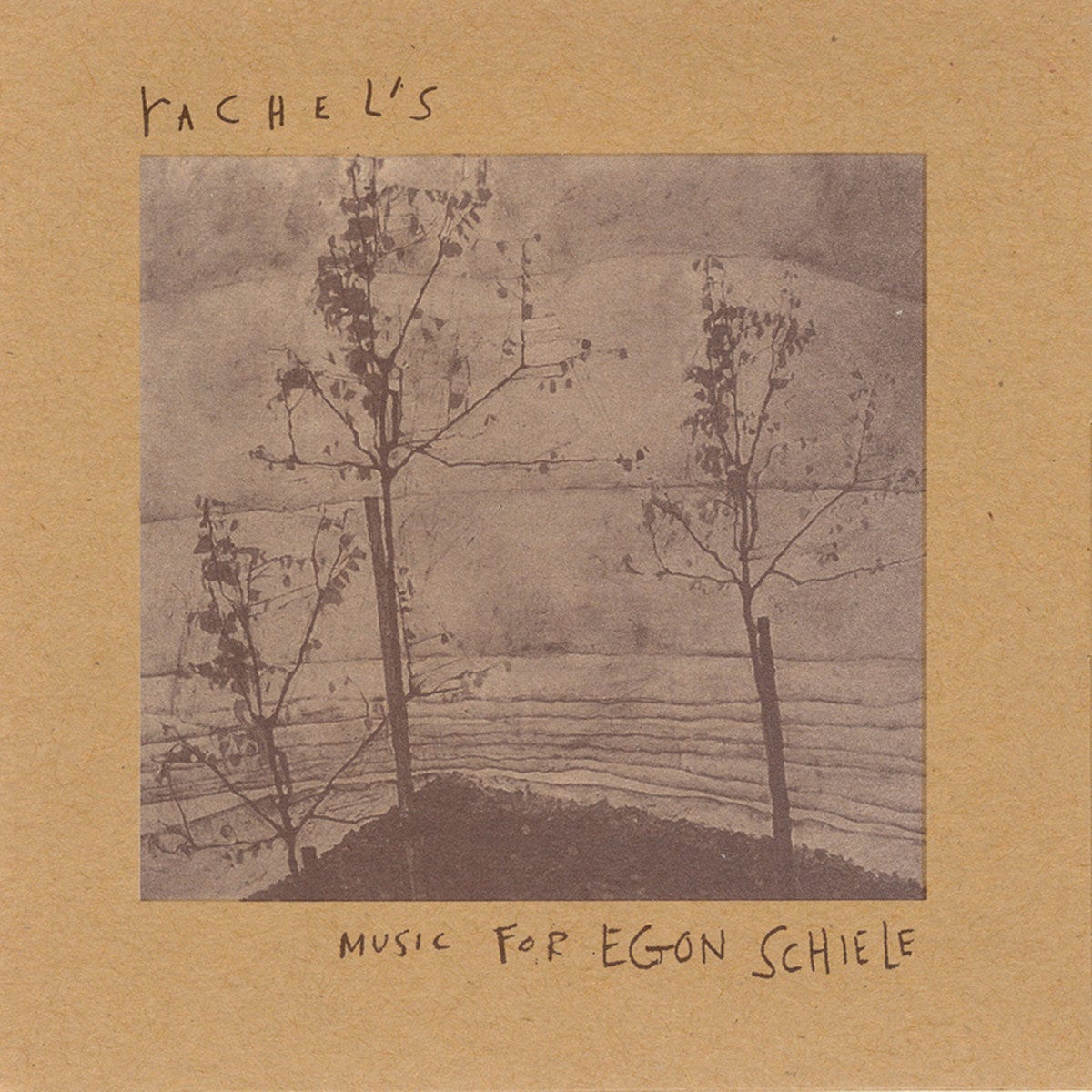

As great as some of these bands were, none it’s the most unlikely group from the city’s scene that I’ve spent the most time listening to, and specifically one of their albums: Rachel’s, Music for Egon Schiele. The album turns 30 this month, and even though I’d suggest their entire discography, the score composed and initially performed for a play about the Austrian painter is one of my lasting musical obsessions. And yes, that’s how you spell the band’s name.

Part of my love for the album comes from my own silly origin story with it: I bought it because I found a used copy for six dollars and had seven left after picking up Slant 6’s Soda Pop * Rip Off which I also purchased used. I had no idea what it sounded like because this was 1999 or so, and the only thing I knew was I’d seen the group’s name in some zine ad and knew the label the album was on, Quarterstick, was part of the Touch & Go Records family. Given that I was still technically a teenager and being able to download music at the time took about an hour per song if you only had dial-up, I took a lot of chances on records just using the little bit of info I had. Sometimes I got lucky, but most of the time I got duds like one or two of the horrible white guy free jazz skronk albums I got because they were on SST when all I knew about that label was Black Flag and a few of the other iconic hardcore/indie bands the label put out. But Music for Egon Schiele changed my whole perspective. I took the album out of its elegant brown cardboard holder that looked more inviting than the clunky plastic cases other CDs came in, and just looked at the cover with a simple, but haunting image of naked tree branches. I’d learn later that it was taken from Schiele’s 1911 Autumn Trees painting, but at that moment in time, I had no idea who the painter was.

That’s one of the things I love the most about the Music for Egon Schiele, and part of why I hope musicians will always be willing and able to make physical copies of their music: holding the record in my hands, even before I listened to it, made me want to know more. Then I put it on, and suddenly, I was once again faced with the unknown: strings, piano, and no singing. Forget the punk rock and hardcore I was expanding from into everything that was just lumped under “indie rock” at that point; I was listening to classical music. It wasn’t like I disliked that or was unfamiliar with the sort of small orchestra sounds that were coming out of my shitty little Sony boombox speakers—I just wasn’t expecting it. Even today, when you look up the band or album on Wikipedia or a site like Rate Your Music, it’s still classified under “post-rock,” which feels a bit misleading, but I sort of understand it.

Rachel’s formed in the early-1990s and, like many of the other Louisville bands I mentioned earlier, had connections to a band that splintered off into basically its own little sub-scene. Jason Noble was in the group Rodan, whose one studio album, 1994’s Rusty, I’d rank somewhere in the top 50-or-so best indie albums of that very fertile decade. Noisy and weird, it was understandable why a band like Rodan would be labeled “post-hardcore” since they screamed enough to frighten off people who probably didn’t have much familiarity with that scene. The band formerly broke up in 1995. Guitarist Jeff Mueller started up bands like June of 44 and Shipping News, while bassist Tara Jane O’Neil has put together one of the more impressive and diverse resumes as a solo musician, band member, and visual artist since the band broke up. Noble had also been dabbling in solo work as Rodan wrapped things up and did it under the moniker Rachel’s, but he’d started meeting future collaborates long before his band broke up. In an article by Alex Deller for the Guardian last year, Rachel’s violist Christian Frederickson recalled first meeting Noble in 1991 on a bus in Baltimore. Frederickson was studying at the Peabody Conservatory of the Johns Hopkins University, while Noble and his friends “were very clearly art students.” Still, they became friendly. “We started going to each other’s events – I’d go up to the art institute for poetry readings or art openings, and he’d come down to the Conservatory for concerts. We started talking about this music he was working on and eventually cobbled together a recording session.”

Handwriting, the first Rachel’s album, came out in 1995. At the risk of overdoing my love for the group, I’d say that it’s actually the perfect entry point into the world of Rachel’s. The first time I heard it was when I realized how Rachel’s reminded me so much of Angelo Badalamenti’s soundtrack work for Twin Peaks. Later on, I’d also recognize the influence artists associated with Brian Eno’s short-lived, but highly influential Obscure Records had on the group’s sound, most notable Gavin Bryars and Michael Nyman, but not when I first listened to Music for Egon Schiele. At the moment, I was just some dummy kid with only a few references, and none of them could connect back to the sparse beauty I was listening to. In fact, if I wouldn’t have picked up that used copy that day, I’m not sure I would have gone and started seeking out other music that could similarly be tagged under “classical.” I don’t think I would have taken the time to dive deep into Philip Glass or Steve Reich, Arthur Russell, William Basinski, Julius Eastman, or so much other music that I consider very important to me today. I actually don’t want to think of where I’d be or what I’d be listening to if I hadn’t had an extra few bucks on me and saw a label name I was vaguely familiar with on the back of the CD.

I’d always hoped that maybe someday, especially as music that shares some of the same influences and DNA as Rachel’s has become increasingly popular, that maybe someday I’d be able to hear the album played live or there’d be a new production of the play the score was written for. Sadly, Noble passed away in 2012 after battling cancer. Richard Grimes, the group’s drummer who was not featured on Music for Egon Schiele (he also played in Metroshifter and other Louisville bands) also died in 2017. I assume when the founder passed on first, it meant the end to Rachel’s, but one of the beautiful things about their music is that it could conceivably live on through new interpolations and performances by other artists, especially Music for Egon Schiele. It feels like part of the contemporary classical canon along with works by Philip Glass, Steve Reich, or Max Richter, the sort of thing that’s just begging to be played in a room by a small group of musicians.

As for the long part opening of this letter that I wrote mostly about Will Oldham, there’s a reason. We had a few hours of chatting, and at some point, I told him that I’d been fascinated with Louisville for a long time, partially because it felt like there was some sort of pipeline directly to and from Chicago from there, partially because I saw so many bands from there play venues where I’d grown up, partially because more than a few bands from Louisville put out records on Chicago-based labels, but also because a handful of the best records from Louisville bands were recorded by Chicago-based producers like Steve Albini or Bon Weston. I’ve also just always been fascinated with scenes, especially ones that could organically produce so many diverse artists and works in a pretty short amount of time. I was surprised when Oldham tied it back to classical music helping serve as a foundation for Louisville’s shape of punk (and indie, post-rock, math rock, or whatever else) to come. Oldham thought for a second, and he told me about how 50 or 60 years ago, there used to be a program that the Louisville Orchestra had that he described as an outreach program in the public schools along the lines of Leonard Bernstein. “And at the same time, ballet was strong here, opera was strong, theater was really strong here. My peers and I were influenced by that.”

I don’t know if Noble would have mentioned this or if any of the members of Rachel’s also thought that the city’s midcentury programs to get people interested in classical music and other art we tend to take for granted these days was part of the reason Louisville went on to have an incredible underground music boom starting in the 1990s. It’s possible that Noble or his collaborators were totally unaware the program Oldham mentioned was even a thing, but I like to think that the fact the city even had them going in the first place helped start something. It’s silly to say it “got in the water,” but it does sort of feel that way. It makes me think those musicians in the ‘90s were part of a lineage or tradition that started before they were old enough to recognize it, that investing a little in the arts can have a lasting impact on a place and its culture.

water from the same source 💙💙

Great piece, Jason. I'm a Kentucky boy and I packed up and moved to Louisville the DAY after I graduated college. In high school we took road trips just to visit ear-x-tacy, two hours each way. It was the greatest record store to ever exist, at least to me, a small town boy. It's long since turned into a Panera Bread, but my moments browsing their racks were my richest, most joyful of music discovery, at a time when I was gaining more listening independence and defining what I loved. I think that magnetism of ear-x-tacy bred a real thoughtful music community. I worked at a hotel and restaurant downtown, and I hired Edward (you listed him as Richard) Grimes. He was such an incredible guy - bright, loving, funny, goofy. At that point he would play some music here and there, and mostly he brushed off his output with Rachel's in a very humble way. Like, oh, that old thing? But I didn't learn just how fucking great they were until several years later. I think Edward would be so happy to know this music lives on. And further to your point, Louisville kept generating talent, with more mainstream breakouts from Nappy Roots, My Morning Jacket, and Jack Harlow.